A MEDIEVAL GRAVE COVER TURNED EXCHEQUER BOARD

Authors: B and M Gittos

Church monuments of the medieval period took many forms such as carved stone effigies and engraved brasses. However, by far the most commonly used monument type was the ubiquitous cross slab. This was a slab of stone with a flat or coped surface used to cover the place of burial. They were originally coffin-shaped in outline and in the case of more burials actually formed the lid of a stone coffin. During the 14th century they lost their distinctive coffin shape and the natural precursor to the ledger slabs which were so popular until the close of the 19th century. Medieval cross slabs would usually have been set flush with the floor of the church, forming part of the pavement but they were also placed on top of tomb chests. The detail worked on the slab was either incised, sculptured in relief or some combination of the two. The design was based on any one of a multitude of different shapes of cross. The choice of cross design

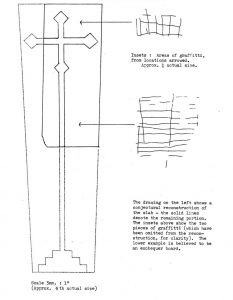

Of the large numbers of such slabs which remain, probably the majority have survived through being re-used as building stone. Thus any repair work to the fabric of a medieval church may reveal previously hidden slabs. During the restoration of St.John’s in 1981, repairs were carried out to the exterior of the south aisle. This led to the discovery of just such re-used slab which had been built into the string below the parapet. The monument is of Ham Hill stone and is incomplete, having been cut down to facilitate its re-use and now measures 40″ x 15½” It was originally coffin-shaped and constitutes the upper half of an incised. cross slab. The design is of a straight arm with lozenge–shaped terminals. The extreme tip of the right terminal was lost when the piece was given a rolled profile of the string course and the left arm of the cross shortened when the slab was cut down to its present size. There is no trace of either an inscription or symbol.

No firm national chronology has yet been established for this type of monument and few examples remain in the locality, making even comparative dating difficult. However, there is in the church at Charlton Mackrell part of a slab of related design. In this case the terminals are larger and triangular in shape with the apex of the triangle pointing towards the centre of the crosshead and the base forming the termination of the cross arm. Even so, the conceit of attaching a straight-armed cross clearly connects, the two monuments.

An extensive view of the appropriate literature has failed to elicit an exact parallel for the design of the Yeovil slab and for the present it remains a unique composition. Other triangular terminals (described as a wedged-shaped by Rosemary Cramp, Ref.1) may be found at Breedon-on-the-Hill, Worcestershire, Ref.2, and Thoresway, Lincs. The latter has been dated c 1225-75 by L.A.S.Butler, Ref.3. The simplicity of the slab at Yeovil and Charlton Mackrell may suggest a very early date but neither slab is coped, a feature often found with monuments dateable to the years following the Norman Conquest. The absence of an inscription woald be unusual in the 14th C. and the slab’s coffin shape is also significant. During the first half of the 14th C, coffin-shaped slabs became less popular and the same trend can be detected in the stones used as casements for brasses and the bases of sculptured effigies. On balance the monument should be assigned a 13th C. date but it may even belong to the closing years of the 12th C.

An interesting feature of the slab is two roughly scratched patterns at each end. They are evidence of ‘the. monument’s re-use prior to becoming building material. The scratches are more than idle graffitti forming a definite pattern of intersecting lines. Desecration of monuments has occurred throughout history but whilst such damage is to be deplored it can offer additional evidence of an archaeological and sociological nature. An interesting cross slab at Skipsea on the Yorkshire coast appears to have two curious flags scratched on it but closer inspection reveals that they are in reality gaming boards for playing “6 Men’s Morris”. The marks on the Yeovil slab are less clear but those at the lower end closely resemble the pattern on the slate found recently during excavations at the Friary in Carmarthen (Ref.4). The Carmarthen slate is claimed to be a counting aid or exchequer board used for reckoning money before Arabic numerals had replaced Roman numerals as the mathematical language. It would seem therefore that the erstwhile memorial was serving as an exchequer board prior to the late 14th C. rebuilding of St.John’s.

The history of this stone may perhaps be summarized as follows : after being quarried on Ham Hill and carved by a local mason, it was set up sometime in the 13th C. to commemorate one of the worthies of the town. The grave slab was subsequently crudely converted into an exchequer board for reckoning the financial affairs of either church or town, or both.

In the traumatic late 14th C. rebuilding of St.John’s by Robert de Sambourne, the stone lost its special importance and was cut up for building material. Its incorporation into the parapet about the south aisle preserved the remarkable evidence of its history until its recent discovery.

The monument was initially deposited on a bench in the south porch. In February 1984, it was placed in the south transept as reported in the previous edition of Chronicle. It is hoped that in due course it will be possible to display the stone properly so that it can receive the attention it justly deserves as Yeovil’s only early medieval memorial and a rare example of a medieval exchequer board.

References

1. Cramp R., A Corpus of Anglo—Saxon Sculpture, Vol.l. 1984.

2. Cutts E.L., A Manual of Sepulchral Slabs and Crosses, pl.XXV, 1849.

3. Butler L.A.S., Ph.D. Thesis, Nottingham-University, 1961.

4. Popular Archaeology, August 1984. p.3.