1986-Nov-Hinton St George

This article came from the Chronicle published November 1986. Pages 113-115

A RE–DISCOVERED MONUMENT AT HINTON ST.GEORGE

Authors: Brian and Moira Gittos

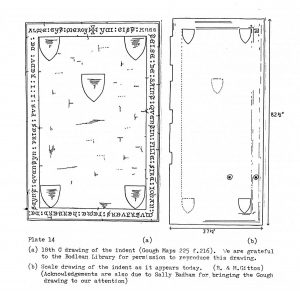

enormous work, usually bound in five large volumes, was the result of many years research and collection of material. However, even in this vast treatise, he had insufficent scope to publish all the monuments of which he knew. He had employed several important artists and draughtsmen to produce illustrations for him but not even all of these drawings were used. The material which remained unpublished is deposited in the Bodlean Library in Oxford. This collection and the examples which went into “Sepulchral Monuments” include many items which have since been lost, re-arranged or “restored”. The Bodlean Library collection includes a drawing of a monument at Hinton St.George, Somerset1. It shows the indent for an early brass from which all the metal had been lost even in Gough’s time. It took the form (see Plate 14a) of a marginal inscription with the individual letters each set in its own indent, between two strips or fillets of brass. In the central panel, were five brass shields. Separate letter inscriptions such as this date from, in general, the first half of the fourteenth century and it is of course still possible to read the inscription from the indent, even after all the brass has been lost. Gough gives the Norman–French inscription as,

“+YCI: GIST: [ANES] TEISE: DE: SAINT: QVENTIN: FI LIE: SIRE: IOHAN: MVTRAVERS:FEME:HERBERD:DE:SEYNT:QVENTYN:PRIES:PVR:I:I:REDV: DE: ALME: EYT: MERCY”

The square brackets indicate that these letters were unclear or covered. For the most part, Gough’s reading indicates that it followed the standard formula for an inscription of this type. However, the part “I:I:REDV:” does not make sense and seems to be a mis-reading of a perhaps worn portion.

In 1644 Richard Symonds2, an Officer in the King’s service had visited Hinton St.George and also recorded this monument, then in the north chapel. He read the inscription as,

“YCI:GIST: [ANES] TEISE:DE: SAINT:QVENTIN: [FILLE] :SIRE:IOHAN: MVTRAVERS: [FEME] : HERBERD: DE:SEYNT:QVENTYN:PRIES:PVR:LI: KE:DV:DE [(S)ALM] E: EYT: MERCY:+”

The first part of this is in complete agreement with Gough’s reading but Symonds later section “PRIES:PVR:LT:KE:DV:DE:(S)ALME:” enables the Gough version to be interpreted. The first “I:” is clearly a mis–reading of an “L” with a high serif and the “R” a mis–reading: of a “K” – letters which are easily confused. Once this has been understood, the latter half of the inscription takes on the usual pattern. The whole inscription may then be translated using modern spellings and letters as,

“Here lies [Anes] teise de Saint Quentin, [daughter] of Sir John Matravers, [wife] of Herberd de Saint Quentin. Pray for her, whom God have mercy on [her soul].”

Symonds and Gough were writing 350 and 200 years ago respectively. Several attempts to identify this indent in the last few years failed and it was assumed that it had been lost in the interval. However, John Batten3 when writing on the Cokers, also mentions the slab, with the comment that

“…it is still there – only instead of being in the church it is outside and converted into a doorstep.”

A renewed search revealed that Batten is indeed correct. The stone now forms part of the pavement before the door of the vestry which was built in 1815. It is now so worn that only a single letter and one stop of the inscription remain clear. Traces of the fillets may be seen in several places and the depressions for the shields may be discerned. A scale-drawing of the slab as it is today forms Plate 14b. A number of pieces have been cut from the side of the slab, perhaps for it to fit against a screen and a foot-scraper has been affixed to it. A comparison of the two drawings show that although the proportions of the Gough sketch are not quite right, the lay-out of the slab is accurate. In particular the rather clumsy positioning of the outer shields in the angles of the inner fillet and the placing of the middle shield above centre are confirmed. It seems likely that the disposition of the inscription around the slab is the result of the way it fitted, once the outline had been drawn, rather than an accurate reflection of its arrangement. The positions of the existing “N” and the stop imply that the stop is the lower of the two following “GIST” and the “N” the second letter of “ANESTEISE”.

Most early indents are cut from Purbeck marble. The reason this has been missed is its current resemblance to Ham stone. The surface has been entirely covered by lichen, endowed with precisely the same hue as Ham stone. A.close examination and cleaning of the surface reveals that it is, in fact, Purbeck marble.

In 1985, a party from the Church Monuments Society and some members of this Society visited Hinton St George to view the monuments,. little realising that the earliest monument by about 100 years was out in the churchyard, supporting a foot-scraper.

References

1. Bodlean Library. Gough Maps 229 f.216.

2. Symonds Richard, Diary of the Marches of the Royal Army during the Great Civil War. Camden Society, LXXLV, 1859.

3. Batten J. Historical and Topographical Coll ections Relating to the Early History of Parts of South Somerset, 1894, p.131.