This article came from the Chronicle published April 1987. Pages: 128-130.

Yeovil Museum Topics – Village Club Brasses

Author: Leslie Brooke

Zoo off they started, two and two,

Wi’ painted poles an’ knots o’ blue

An’ girt silk flags . . .

An’ poles a-stood so thick as

The rushes stood beside a river (Ref. 1)

Members of the Museum Working Party devote one day a week (sometimes more) to curatorial work at Yeovil Museum. Since the last issue of ‘Chronicle’ they have, among other things, refurbished a recessed wall case in the lower gallery, making it damp-proof and lining it with hessian, in order to provide a more effective display of the Museum’s very fine collection of village club brasses, which were previously shown in a desk-type case in the upper gallery.

Village benefit clubs were among the oldest friendly societies which flourished, before the ‘welfare state’ took over, for the alleviation of the sick and needy. These clubs were particularly strong in agricultural districts and in small country towns in the southern half of the country, prior to the establishment of larger, national societies, such as the Oddfellows, Foresters, Druids, Rational, and many more, which eventually absorbed or superceded them. But many survived until the first world war, and a few remained even after that.

Ancestry of the village club can be traced back to the medieval gilds – in addition to Anglo-Saxon frith gilds, there were religious and craft gilds. By the end of the fourteenth century, practically every craft or trade was represented by a gild and, although mainly established for secular objects, they also possessed strong religious attachments and represented genuine fraternities.

Here, in Yeovil, a chantry in St.John’s church came about as the direct result of a gild or fraternity being formed for its maintenance and for assisting the needy. This was because of a provision made by John Woborn, in founding the almshouse bearing his name, for the establishment of a brotherhood ‘of the parishioners of Yeovil and all others . . . to provide for the sufficient sustentation of the poor aforesaid’, and this was known as the Fraternity of the Name of Jesus’. (Ref.2).

When the religious gilds were suppressed in the reign of Edward VI, village friendly societies seem gradually to have come into being, and the spiritual foundation on which the ancient societies rested lived on in then. With headquarters usually established in the village inn, these societies were formed to ‘join together in an orderly, peaceful, and amicable Manner to provide for the Support of each other in time of Sickness, Lameness, or any Incapacity, of getting a Subsistence’. (Ref.3).

Once a year members got together for a ‘share-out’, when ‘surplus’ funds were devoted to ‘The Club Feast’. This was preceded, in the majority of cases, by a service in the church and a perambulation of the streets, which was known as ‘The Club Walk’. This procession was often accompanied by a large and elaborately embroidered banner, and sometimes with musical accompaniment, while club officials and members carried poles on which were mounted knobs or spear-like emblems of a particular pattern adopted by that particular society, most of those which survive being of brass, though there were a few which were made of wood. In certain clubs the officials were distinguished by a brass of a different design to those of the members, as at Stoke St. Michael.

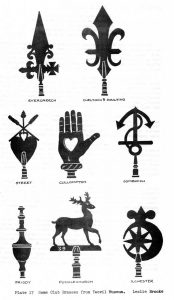

It is examples of these ‘club brasses’, which form the display now mounted in the museum. Undoubtedly the designs, which are many and varied, derive originally from spear-heads, or maces. A sample of the brasses on show is illustrated here. The heads of a large number are made of sheet brass set in a tubular base which fit over the end of a pole, and frequently exhibit distinctive patterns appropriate to the society represented.

Ilchester, for instance, displayed the town arms – an eight-pointed star in a crescent, and Combwich shows an anchor, suitable for the name of the inn, of that name at the tiny port at the mouth of the Parret, where the society met. At Street, the Hearts of Oak Club, showed a complicated design figuring two hearts and an acorn.

Three-dimensional forms, similar to the one illustrated for Priddy, were adopted by many clubs, and are reminiscent of knobs on brass bedsteads. One heavy, solid brass, symbol in the form of a hand pierced by the conventional heart shape, well modelled with finger nails shown on the back, and an out-stretched thumb, was made for a Cullompton society.

The club at Chelynch and Doulting met at the Fleur-de-lis Inn, if the design on their large brass is anything to go by, while at Evercreech the symbols at each side below the decorated spear-like head, show a fleur-de-lis and a cross patée. The one example from Gloucestershire, of a stag for the Pucklechurch society, suggests they were based at the White Hart, and the figures 39 which are stamped on it indicate that this belonged to, and was carried by, the member to whom that number had been allocated.

These are only a small sample of ‘token’ brasses held at Yeovil Museum. Should any member possess photographs showing local club walks and the poles being carried, Mr.Hayward, the editor, or the writer, would like to know of them. Finally, there is a humorous story about a Club Walk in ‘Cluster-o-Vive’ by John Read (No.11 in the Somerset Folk Series), entitled ‘Adam Genge and the Lamb’s Wool’ – Lamb’s Wool being a potent kind of punch!

Leslie Brooke

References :

- From William Barnes’s poem ‘Whitsuntide an’ Club Walken’.

- Woborn Almshouse regulations, John Collinson, History of Somerset, III p.211.

- Rules, etc., The Fullers’ Friendly Society, Taunton, 1751.