This article came from the Chronicle published April 1987. Pages: 131-134.

An Archaeological Investigation of the New Library Site, Yeovil – Part 2: The Finds

Further Reading: Yeovil – New Library Site – Initial Archaeological Investigation

Authors: Brian and Moira Gittos.

The first report on the library site Investigation(Chronicle Vol.5 p.102-108,1986) charted the progress of the investigation and described the main features. There had been little opportunity for post excavation work on the finds. Preliminary work has now been completed and full expert analysis is underway. The following is a summary of the initial results.

There were 1,060 finds of which 145 were pieces of bone; 132 pieces of clay pipe; 59 shells; 79 fragments of glass; 67 bricks or brick fragments; 22 pieces of stone; 22 metal objects and 446 sherds of pottery. These artefacts were not evenly distributed, with some features contributing a large proportion of the total finds. The most extreme example was the midden pit from which 169 pottery sherds were recovered. Taken together with the 77 sherds of probably related material from an adjacent trench, this accounted for more than half the pottery found on the whole site. Many of the clay pipe pieces came from the same small area but the largest group of clay pipe fragments belonged to the cinder pit at the north end of the site. Bone was recovered from both these areas and a significant collection was also recovered from the drain below the market road. A broad date range was represented by the finds, from the medieval period to the present day, but the bulk of the pottery and pipes probably dated from the end of the 17th/beginning of the 18th centuries.

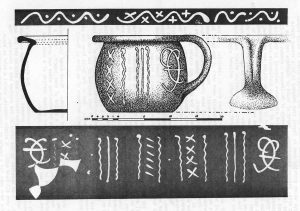

The bulk of the pottery was a fairly rough earthenware with variable glazing according to the potter’s whim. This glazing varied from a biscuit colour to green and dark brown with occasional dark streaks and flecks caused by the iron rich inclusions in the fabric. Chamber pots were well represented in this group with their flat rims and upright walls. The smallest vessels were ointment pots one of which was the only intact vessel from the site. At the other extreme there were fragments of the very large bowls called pantheons which could have found a multitude of uses in the kitchen. Perhaps the most interesting type represented was the chafing dish. Pieces of at least three were found, They consisted of a shallow bowl on a hollow pedestal foot, the base of the bowl being pierced. A light was put in the pedestal and heat rose through the holes such as to keep warm, dishes of food placed in the bowl. This system was important at a time when kitchens were often in separate buildings and when all the courses of a meal were placed on the table together. Such vessels would have been more highly prized than humble kitchen wares.

A number of potteries were operating in Somerset in the post-medieval period such as Wanstrow and Nether Stowey. The most prolific and also the most local were kilns at Donyatt. Some excavation was carried out there in the 1970’s but to date only a brief interim report has been published (Excavations at Donyatt and Nether Stowey, Somerset, Donyatt Research Group, 1970). Whilst some of the material is probably from Donyatt, this does not always seem to be the case. Some of the earthenware is highly decorated with painted on slip in a wide

Many of the pieces of bone were small and not easy to identify. Of the pieces which have been identified the most notable were part of the lower jaw of a pig, a cow’s incisor and the skull of a rabbit. Many of the bones showed signs of butchery. The more obvious of which came from the brick-lined drain presumably from where it ran past the meat market. Other bones with knife marks were found in the more domestic areas, such as the midden and cinder pits. Probably the most significant of the organic remains as a horn core. This is the light structure which supports a horn and attaches it to the skull. The piece recovered comprised a large portion of core together with a small section of skull. The core showed clear evidenne of cut marks where the horn had been stripped away. The horn itself was extremely valuable for making many items from buttons and combs to cups. Horn cores are commonly found on both horn working and tanning sites, the two industries being closely related.

Of the 132 fragments of clay pipe, 79% were pieces of stem none of which bore makers’ marks, although they are occasionally found on stems. Unfortunately many of the bowls had no identification, but two makers’ marks were noted which each occurred on more than one pipe. “P” in a circle was present on the side of several bowls and a small “W” was located where the spur met the bowl. Neither of these makers’ marks is readily identifiable. Most of the pipe bowls had a flared rim, dated by Oswald. (BAA Vol.23,1960) between 1690 and 1730. A single example had moulded decoration on the bowl of a type current in the 2nd half of the 17th c. The earliest of the pipes was discovered at the base of the long stone wall and it is dated by its shape to the last quarter of the 17th c. It bore the letters “ID” on the base of the bowl. One of the bowls from the midden had finger prints in orange paint, presumably evidence of an 18th c. Yeovil decorator!

Most of the glass was derived from wine bottles. These dumpy black onion-shaped bottles seem to have been used over a period of some length. Only a single neck was recovered, the other pieces representing sides and predominantly bases. A chance find by the Site Agent was a large portion of a hand made drinking glass, which was probably of 18th C.date.

A variety of building materials were represented. Ham stone was found in different areas of the site. Blocks were present in the long stone wall and it was also used for a rain runnel, drain construction and capping and the top of well No,3. Lias occurred in the setts of the roadway and a doorstep. The older bricks were all hand made. A single example, almost a cube in shape, had apparently been used for a hearth or fireplace and other examples had been used in the construction of wells and a drain. The well bricks had been manufactured for the purpose, being key-stone shaped. These hand made bricks were probably of local manufacture as several brick makers are known to have worked in the town and part of St.Michael’s Avenue was formerly named Brickyard Lane. Perhaps the most interesting item of building material was a portion of green glazed ridge tile. These were in use from medieval times but the example found was post-medieval. They are shaped like an upturned “U” and would straddle the ridge of the roof with a decorative cresting uppermost.

There were few small finds and no coins. This may have been due to the nature of the site. In a conventional excavation, the investigator removes the earth and is in a position to examine it for finds. However, on the Library site, very little examination of this type was possible, the task being conducted by observation of the sections revealed by the contractor’s trenches.

By far the most significant of the small finds was a complete bronze buckle decorated with chevron markings, which may have been filled with a contrasting metal, perhaps silver. It is believed to be of medieval date and was discovered towards the top of the colourful pit. The finds from the colourful pit should be considered as a whole. It was located near the South Street end of the site, at the western limit of the area uncovered and close to No.4 well. Its fill was streaked with red and black from burnt debris, much of which had reverted back to the clay from which it had originally derived. Some samples of this fill were recovered and proved to be shapeless lumps of clay which had been fired or burnt. They contained many holes, the spaces left by the straw which had formed part of the composition. It is possible that such material could originate from a timber-framed building destroyed by fire but perhaps the more likely explanation is that it is clay waste from an industrial process such as metal working or pottery manufacture. It was from this exciting context that a very different type of pottery was identified. It was of dark grey, very sandy fabric with small neat triangular section or turned-over rims and some evidence of green glazing. It probably dates from the 14th C.

This brief summary of the finds from the Library site has been compiled to record the information currently available. However, at the time of writing, the material has been submitted to Taunton as the first step in obtaining formal reports on the pottery and clay pipes, subject to adequate funding being obtained. When this activity has been completed it will be possible to re-assess the archaeological evidence on the basis of the dating of the finds. Ultimately, all the data will be collated in a final report.