This article came from the Chronicle published November 1986. Pages 102-108.

Yeovil – New Library Site – Initial Archaeological Investigation

Further Reading: An Archaeological Investigation of the New Library Site, Yeovil – Part 2: The Finds

Author: Brian and Moira Gittos

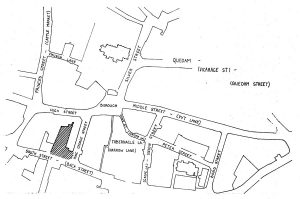

The decision to build Yeovil’s new public library, adjoining the old building, on a car park off South Street, provided the opportunity for an archaeological investigation of an important area of the town, just within the boundary of the mediaeval borough. The location of the roughly “L” shaped plot is shown in the sketch map below,

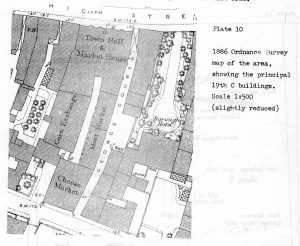

The history of this area of the town has proved difficult to piece together. The earliest maps which show useful detail date from the beginning of the last century, with Mr.Watt’s Map of Yeovil being dated 1805, Manuscript sources have been researched by Mr.Leonard Hayward and show that there was a public house called the King’s Head at the northern extremity of the site, fronting the High Street, one of a group of four public houses which used to be situated along the south side of the High Street – and some cottages

The next most important development was the conversion of the Cheese Market to the town’s Fire Station in 1913, when it was moved from cramped premises in Vicarage Street. Major upheavals were to follow, with the construction in the 1920’s of a new road, linking South Street to High Street — King George Street – just east of George Court. With the new highway came the Municipal Offices and Library of the present day. This work was completed in 1928 and only seven years later a disastrous fire destroyed the Town Hall.. The Corn Exchange suffered bomb damage during the war and, presumably associated with this, is the plaque set up to commemorate

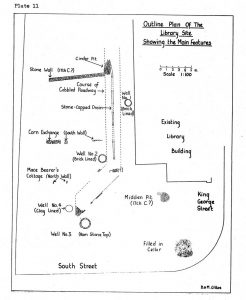

The first feature which was revealed was seen only by the contractors, who had fortunately photographed it. It was a complete cobbled lane, lying north-south, close to the west wall of the existing library. First thoughts that this was George Court were dispelled by closer examination of the 19th century maps. George Court had, in fact, been obliterated by the 1920’s campaign of building and the re-discovered roadway corresponded to the main access through the markets. (For this and other features noted during the investigation, please see Plate.11 opposite). Just east of the roadway and hard against the Library capped with a slab of ham stone. The “U” section was wider towards the top. The trench in which the drain had been laid had. been limed and the drain itself contained silt which varied in content and depth along its length. Towards South Street,

The second well was discovered early in the trench cutting sequence. It was situated on the west side of the cobbled roadway, opposite the corner of the Library. It was entirely constructed from bricks which were hand made and of a tapered design specially suited to well construction. There was an elaborate well-head which had been broken up by the excavator but was also of brick and probably rectangular in shape. However, these bricks were more modern in appearance and it seemed that this well-head had been added to an earlier well. Again the well was rapidly excavated and back-filled with concrete such as to give no opportunity to assess its contents. Nevertheless, it did prove possible to recover about 50 of the hand made bricks from the well top and it is hoped that they can form part of a display of finds from the site to be set up in Yeovil Museum.

Trenches at the south-east corner of the site revealed much burnt material of a very modern nature, close to the surface which probably represented no more than debris from a bonfire of material from the demolished Fire Station. There was considerable disturbance of the ground, to a depth of about 15′, in the south-east corner and it was assumed that this represented a filled in cellar beneath the three storied building noted above. Also in this area, the substantial footing of a stone wall, faced on its eastern side, were revealed. This was in a suitable position to be the east wall of the revealed Market/Fire Station.

The step in the south wall. of the Library is there because it was built around the then existing Fire Station and it remains as a mirror-image of that part of the vanished building. Just south of this step, the contractor’s trenches revealed a fortunate discovery. It was a rubbish pit, probably dating from the 17th century, which we have christened the “midden pit”. From it was recovered almost as many artefacts (mostly pottery and glass) than from the whole of the rest of the site put together. Furthermore, it produced the two most complete vessels which were found, namely a green-glazed egg-cup and a chamber pot in 26 pieces. The chamber pot had evidently been thrown into the pit whole and then crushed by other material being deposited on top of it. It is of poor workmanship with crude slip decoration and inferior firing of the clay. The base is very thin and a small circular hole has been punched through it. This would account for its being discarded whole, as being no longer fit for its purpose! Another significant find from the midden pit area was one end of a green-glazed ridge tile. Both sides were broken but it was crowned with low, scalloped cresting as opposed to the more usual high, dagged profile. The glazing is only on the outside and mainly on the sides. It could certainly have graced a mediaeval building but how recently such tiles were still in use will require further research.

The most substantial structure revealed by the excavations was a stone wall at the north end of the site. Its dimensions were at least 29″ 6″ long by 4′ deep. The alignment was at a slight angle to the existing Library wall, more indicative of a building fronting the High Street than South Street. Near the base of this well-built wall was discovered the earliest of many clay pipes found distributed over the site. This pipe,has been tentatively dated to the first half of the 17th century and it may provide dating evidence for the wall. The alignment and position of the wall did not correspond to any of the buildings known to have occupied that part of the site, from the maps which have been described. The wall appeared to stop at the edge of the roadway but was visible westwards as far as the excavations went.

At a later stage, more of the car park tarmac was stripped, to reveal another section of the course of the cobbled roadway. This turned out to be something of a surprise. Instead of proceeding straight southwards, to meet South Street at right angles, it turned wouth-west and came to a well defined end without ever reaching the road. The mettled end of the roadway was the only complete part which we were able to examine, the rest being rapidly removed by the contractor. The setts, however, were not discarded as they are destined for re-use in the restored church path at Queen Camel. The appearance of the end of the roadway is shown in the accompanying photograph (plate 12). There was a shallow gutter down the edge of the road, with a line of bricks beyond that. The gutter was interrupted at one point by a square block of Ham stone, flush with the kerb. This seems illogical but it may have formed the base for a wooden post. Near to the end of the roadway and also visible in the photograph, is the top of the third well. We were fortunate in having the time to clean the top of this well which unlike the previous two was of Ham stone. However, careful cleaning revealed only two or three courses of stone around the well top and neither stone nor brick beneath. This well was dug out by a mechanical excavator and it could then be seen that it had been lined only with clay, as the fill fell away from the sides during its excavation. Again there was no opportunity to examine the fill. It was excavated to a depth of about 13 feet.

One further well was discovered, on the day before we were due to finish our supervision of the site and the steel erectors moved in to begin the next phase of the construction. The fourth well was situated just west of the end of the cobbled roadway. Its top was not observed but it appeared to be clay lined, like the third well. Many pits were revealed, mostly smaller than the midden or cellar pits. One near the east end of the long stone wall was largely filled with cinders and another, just west of the

Traces of two further east-west walls were noted. One corresponded to the south end wall of the Corn Exchange and the other was probably

That concludes the main features which were noted. It is intended that a detailed account will be published. when the evidence has been more thoroughly analysed. At every stage were only too aware that we were recording and interpreting only a small fraction of the evidence which would have been available to a trained archaeologist. Even to obtain the amount of evidence which has been gleaned, involved a considerable effort. It took 25 visits to the site; the production of 50 sketches and drawings; the taking of some 128 photographs and the collection of 56 bags of finds. We would like to acknowledge the excellent co-operation which we received from the contractors, in particular the Site Director, and the Site Foreman. We were given encouragement and loaned equipment by Mr.Dennison of the County Archaeologist’s Department. Especial thanks are due to Leslie Brooke and Leonard Hayward for their unfailing help, encouragement and knowledge and to the other members of the Gittos clan, who all helped in the venture, from holding end of a tape measure to washing the pots.

In 1927 Alderman W.Mitchelmore, former Hon.Curator of the Wyndham Museum wrote,

“Why have archaeologists paid so little attention to Yeovil”

Brian and Moira Gittos