1997 – pg64-66 – Beast Head in Hardington Mandeville Church

This article came from the Chronicle published October 1997. Pages 64-66

ANGLO-SCANDINAVIAN? BEAST HEAD IN HARDINGTON MANDEVILLE CHURCH

Authors: Brian & Moira Gittos

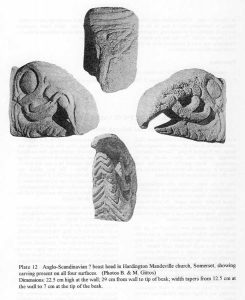

Mounted on the north wall of the sanctuary of St Mary’s church, Hardington Mandeville, is a stone carved in the form of a beast head. It has been placed so that it acts as the corbel supporting a small shelf The head is carved on all sides with an open beak and large, bulbous eyes. The upper mandible is hooked, like a bird of prey and two curly tendrils are shown in the open mouth, like a forked tongue curled back on itself. Small tendrils, with incised outlines are shown above the upper mandible on the east side. The eye socket is penannular and has curls at the two ends. There is an incised pattern of fines on the top of the head and a regular pattern of ‘V’s on the under side. The main features can be seen in Pl. 12, which shows the head from both sides and from above and below.

The nave and chancel of Hardington church were re¬built between 1862 and 1864 and, presumably, the stone was placed in its present position at that time. The church guide informs us that the Romanesque arch on the north side of the chancel was carved by Rev. John Hancock, Vicar of Haselbury Plucknett. This accomplished cleric also carved the ten corbels which support the chancel roof. The beast head is not mentioned in the church guide, nor in any other source of which the authors are aware. It might, at first sight, be considered that this too was a product of the Rev. John Hancock but close examination suggests otherwise.

The head is carved from a coarse grey stone containing ooliths but which does not resemble any material found locally. However, the front few inches of the lower mandible have been carefully repaired with a small piece of Ham Hill stone, carved to match the pattern. The western side, facing both congregation and visitors, is more sharply finished and largely unweathered, whereas all the other surfaces show distinct weathering. This strongly suggests that this more visible side has been re-cut and improved. The suspicion draws substance from the realisation that the patterning on the upper surface, whilst respecting the eastern face, is interrupted by the sharp corner of the western face. Clearly material has been removed to allow re-cutting of this face in fresh stone. For this reason the weathered, but unaltered, eastern side has been used for the cover illustration. It is, however, possible that the detail on the western face largely represents the original design, despite being re-cut. Nevertheless, it is sufficiently unreliable to omit it from any discussion of style or dating.

An important feature of the head is the presence of the distinctive curly ended tendrils of the tongue and upper mandible and the similar termination of the border around the large, unpierced, eyes. The use of such tendrils is usually associated with the Scandinavian Ringerike style, most commonly illustrated by the fragment of a Scandinavian tomb found in St Paul’s Churchyard, London.1 The closest parallel to the Hardington sculpture so far discovered by the authors is a beast head carved on a maple wood walking stick from Lund, Sweden. This shows similar use of tendrils along the top of the mouth and similar large, bulbous eyes.2 This object is dated between 975 and 1050 A.D. and, on this basis, a tentative date of c.1,000 A.D. is suggested for the Hardington sculpture.

The fully three dimensional carving of the head, with no load-bearing platform on its upper surface, suggests that it was not a corbel but was intended to project from a wall in a dramatic manner. At Kilpeck (Herefordshire) beast heads with wide open mouths and coiled tongues project from the tops of the nave quoins of a Romanesque church whereas at Deerhurst (Gloucestershire) rather more solid beast heads (prokrossoi) project above three surviving doorways of the Anglo-Saxon church.. Neither provide a stylistic comparison for the Hardington head. Those at Kilpeck belong to the work of the highly individual Herefordshire School of Sculpture. Those at Deerhurst are severely damaged but are massive in design and may never have had much surface detail. They belong with the simple, massive, Anglo-Saxon masonry of the church.

There remains the question of the beast’s provenance. It is possible that it was brought to Hardington from elsewhere, specifically for incorporation in the 1860s building – conceivably even by the Rev. Hancock himself – but it is, perhaps more likely that it was discovered during the demolition of the previous building, and then repaired and improved before being set up as it appears today. The re-cutting and repair may well be Hancock’s work. If the sculpture does, indeed, belong to Hardington, then it may be the only remaining fragment of an elaborately ornamented Pre-Conquest church. The fact that the manor of Hardington was a royal possession prior to 1066 would make this at least plausible.

Sculpture of this type is exceedingly rare in a south-western context and could have important implications for Scandinavian settlement in the area. Research continues.

Footnotes

- Graham-Campbell, J. & Kidd, D The Vikings, (1980), p.172

- Roesdahl, E, Graham-Campbell, J, Connor, P. & Pearson, K. eds The Vikings in England and in their Danish Homeland, item B42, p.34.