Book Reviews

‘Roman Britain and Where to Find It’

Brian Gittos (December 2020)

Allen, D. & Bryan, M., Roman Britain and where to find it (Amberley Publishing, 2020), 256 pages, 96 colour illustrations, 4 black & white plans, paperback, £19.99, ISBN 978 1 4456 9014 8 (also available in hardback and as an E-book).

One of the good things which happened during the first lock-down due to the Coronavirus this year was that some books which were already in progress continued to be published. One such example was Roman Britain and where to find it which appeared in May. It is essentially a guide to accessible Roman sites in England Wales and Scotland, in the guise of a gazetteer set out in nine chapters. Two cover Wales and Scotland and seven deal with England, subdivided into six broad regions and a narrow zone bordering Hadrian’s Wall. Each region comprises a group of neighbouring counties with the exception of Somerset and Hampshire, both of which are split between adjacent regions. The gazetteer encompasses both the sites and the museums where artifacts are displayed. Also included is a helpful glossary, a brief list of relevant people (both Britons and Romans), a timeline for Roman Britain, suggestions for further reading and an index of sites. It fulls a surprising gap in the market and will render Britain’s remarkable Roman heritage much more accessible to the general public.

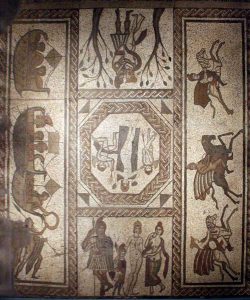

Each chapter opens with a map showing the site locations in that region, which are potentially useful when planning a personal itinerary. The book is well illustrated with not only clear views of individual places but also many of the more significant objects. From Scotland there is the spectacular bronze military parade helmet found at Newstead and held by the National Museum of Scotland. Another example of a special object is the enamelled bronze bowl, known as the Staffordshire Morlands pan, which may be a Roman souvenir of Hadrian’s Wall. The sites covered vary enormously, ranging from the extensive and upstanding walls of Caerwent Roman town (Glamorganshire) to the subterranean Dolaucothi goldmines (Carmarthenshire). Nearer to home, the Cerne Giant is included as it seems to represent the Roman god Hercules but with a health warning that no mention of it is known before the 16th century. The story is related of the finding of the of the Low Ham Villa by a farmer burying sheep. The villa was subsequently excavated and the very fine mosaic depicting the legend of Dido and Aeneas is the centre piece of major display in The Museum of Somerset at Taunton Castle (below right).

The town house with its mosaics in Dorchester is illustrated and, also in Dorset, there is the temple site at Jordan Hill. This entry is of particular interest because it reveals the fate of some of the finds from the ill-recorded 19th century excavations. They went to the Pitt Rivers Museum and were moved to Oxford, where a couple of items have been displayed amongst a much larger ethnographic collection.

The gazetteer entries are filled with interesting and informative facts, often succinctly incorporating the fruits of recent research, making the book a useful shortcut to current thinking. This is the sort of book for dipping into, to make ever more discoveries, rather than reading right through at one go. It will also be useful to have with you when travelling or to guide the planning of future trips.

The authors are very familiar with the material they present, describing how they ‘thoroughly enjoyed seeking out all these sites again’ and the impressive extent of their fieldwork is evident in the entries. However, such familiarity can occasionally be a problem when communicating the information. A case in point concerns the Balkerne Gate in Colchester. In the Foreword (by the best-selling historical novelist Ben Kane), there is mention of there being ‘an excellent pub in the top half of the Balkerne Gate at Colchester’ but no pub is visible in the picture of the gate on p. 11, which has two arches rather than just the one mentioned in the gazetteer. Unfortunately a detailed knowledge of the landscape and how the gate was constructed is being assumed. One of the arches in the picture gave pedestrian access through the gate and the other only provided an entrance to the flanking south tower. The pub, now appropriately called the Hole in the Wall, is out of sight to the right. It was built over the site of the north side of the gate and Mortimer Wheeler had to tunnel beneath it to examine the gate’s foundations.

However, such a detailed observation should in no way be allowed to detract from the usefulness of this fascinating and demonstrably valuable work. Available at an extremely reasonable price, it is thoroughly recommended to YALHS members, who should remember to take it with them on their travels, when it is safe so to do.