2005-pg19-22_St Urith of Chittlehampton

This article came from the Chronicle published November 2005. Pages 19-22

St Urith of Chittlehampton

Authors: B&M Gittos

The north Devon village of Chittlehampton is situated between the rivers Taw and Mole, about six miles west of South Molton and about nine miles south-west of Barnstaple. The church has what is almost certainly a unique dedication, to St Hieritha (also spelt Uritha and Urith), see Plate 7. For convenience, the last of these versions will be used here. St Urith is a legendary figure attributed to the 6th century AD. She is said to have been a Christian virgin beheaded by villagers, using a scythe, on the instruction of her evil stepmother. A spring is said to have gushed from the ground where her head fell and flowers bloomed in what was previously barren ground. In the 15th century, a monk of Glastonbury wrote a poem about St Urith in his commonplace book and this source provides the only surviving account of the legend. The survival of Chittlehampton’s dedication to St Urith is surprising since in 1330, Bishop Grandisson of Exeter conducted a purge of unusual dedications throughout his diocese. Only those churches able to write a full account of their saint were permitted to retain the dedication.

Chittlehampton claimed to possess the relics of St Urith and her tomb provided a focus for pilgrimage, her feast being celebrated on 29th June. Images of St Urith can be seen carved on the 15th century pulpit at Chittlehampton; in stained glass at Nettlecombe (Somerset); on a font at North Molton (quite close to Chittlehampton) and painted on the rood screens at Ashton and Hennock, both in Devon. This provides evidence for the establishment of the cult of St Urith. Also in Chittlehampton is a holy well (really a spring) known as St Teara’s well, Teara being yet another version of the saint’s name. Traditionally, the well marks the site of the saint’s martyrdom. It lies to the south-east of the church and is now a crude, concrete, recess (Plate 8). However, the recess does retain a small, shallow, stone basin which may be of some antiquity. On 10th July 1954, the then Bishop of Exeter led a procession of pilgrims from the well to the church, to rehallow the tomb of the saint.

The presumed site of St Urith’s shrine is a curious feature of the church (Plate 9). It takes the form of a small chamber in the angle between the north transept and the chancel and is open to both, through two tall archways. It is shown on the accompanying plan (Plate 10) And the general layout of the east end of the church could be explained as being strongly influenced by the presence of the saint’;s shrine.

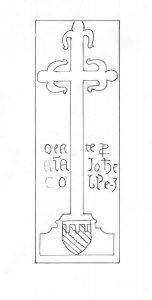

The grave slab which now rests within this recess was moved to its present position during the restoration of the church in 1872, having previously been located in the floor of the north transept. In 1954, in association with the rehallowing, it was raised and placed on a low plinth. It would appear that the grave slab was placed in the recess under the misapprehension that it once covered the remains of the saint. However, an inspection of the slab (Plate 11) revealed it to be a coherent monument of the late 14th or early 15th century. It is rectangular and has incised upon it a straight-armed cross with relatively large, chisel ended, fleur de lys terminals. The cross stands on a base which derives its shape from an architectural moulding and encloses a shield of arms (a bend, invected, cotised with a label of three points). Across the middle of the slab is a blackletter inscription, rather crudely inscribed, which appears to read,

Orate p[ro] a[n]i[m]a Johe Cobley

i.e. ‘Pray for the soul of John Cobley’. The style and incising of the inscription indicates that it was probably an original feature of the monument, rather than an appropriation.

The slab has been discussed by two writers. W.H. Hamilton Rogers (The Antient Sepulchral Effigies and Monumental and Memorial Sculpture of Devon, Exeter, 1877, p.256) listed it as an example of a ‘coffin shaped stone’ as follows, ‘Also at Chittlehampton with a cross florée resting on a base, on which are the following arms, a bend engrailed, cotised and this inscription, ‘Orate pro aia Joh: Doble’. The Rev. Andrews, in his 105 page article on Chittlehampton published in the Transactions of the Devonshire Association in 1962, gives a positive identification for the monument,

At Brightley, John Coblegh who succeeded his father in 1492 at the age of 13 married Joan Fortescue (of Wymston), and it is her epitaph, ‘Orate pre anima Johe Cobley’ which is rudely cut across the stone bearing a foliated cross formerly in the north transept of the church together with the arms of Fortescue.

In a footnote, he adds that it is possible that before its use for Joan Coblegh, it covered the saint’s remains.

Plate 10 To Follow

There are a number of problems with Andrews identification of the slab. The John Coblegh who married Joan Fortescue died in 1542 and presumably Joan herself also lived well into the sixteenth-century. This is too late for the style of the inscription or the monument to which it appears to belong. The arms on the shield lack colour and although they could be interpreted as Fortescue, the bend is invected rather than engrailed and it has the addition of a label of three points. This is an heraldic difference used, normally, by the eldest son during his father’s lifetime and then dropped. This would mean that Joan was displaying the transient arms of an individual rather than those of her family or her husband’s. In the medieval period a woman did not bear arms in their own right and used the arms either of her father or her husband. The Coblegh arms also included a bend engrailed and the difficulty of interpreting the arms on this shield may simply be due to a lack of information about the bearings born by different members of these minor gentry families.

However, although the abbreviation ‘Johe’ could, conceivable, represent the female form of the name (Johanna), it is much more likely to represent the male form, Johannes. In this case, given the date of the cross, we should be looking for a John Coblegh dying about 1400. Unfortunately, the earliest member of the Coblegh family who actually held the manor of Chittlehampton was the John Coblegh who died in 1492. He was the third husband of Isabella Brightlegh. She died in 1466 and John married for a second time, Joan Pyne. The monumental brass on the floor of the nave, by the pulpit, commemorates this John Coblegh and his two wives (Plate 12). A second brass commemorates his parents, Henry Coblegh (ob.1470) and Alice Coolworthy. It would appear that the slab now used to commemorate Saint Urith was originally the monument to one of Henry’s ancestors.

The north transept of Chittlehampton church was restored in 1955 as St Michael’s chapel. It was formerly the Gifford chapel and it contains a large monument, against the north wall, erected by John Gifford (died 1665) for his grandfather and five generations of his family. There was also a second Gifford monument in this chapel which was dismantled in 1872 to make way for the organ (which has since been removed). All that remains of this monument, which commemorated Grace Gifford, is her reclining effigy against the wall in the north east corner of the chapel (Plate 13) and an inscription panel on the wall above. It records that she died in Sherborne in 1667, two years after her father, allegedly from the effects of pricking herself with a fern! This story probably stems from the object she is holding in her left hand but this is much more likely to be a symbolic palm than a fern frond. The monument is not well carved and was produced quite locally, since the material is Somerset alabaster. This material can be recognised by its heavy contamination with brown salts and is quite distinct from the purer material produced by the main deposits in Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire. In research carried out since 1984, Dr Ron Firman (formerly of Nottingham University) has identified the extensive use of alabaster from deposits on the Severn Estuary at Blue Anchor Bay. The material was only worked for about 100 years, spanning the 17th century, and the best documented example is the font at Williton. Grace Gifford’s effigy is one of a group of Somerset alabaster monuments which have been recognised in north Devon.

Despite the significant changes which the church at Chittlehampton has experienced through the centuries, it still retains important evidence which would repay further study.